Rocky shores around New Zealand have areas in water depths of between about three to eleven metres where there is little (and sometimes no) kelp. In a number of places these areas only have algal felts or low turfs and many kina (sea urchins). Initially this was thought to be the natural state. Researchers here and overseas have since found such barrens are the result of intensive browsing by sea urchins that prevents kelp regrowth. (April 2016)

The sea urchin numbers have increased because the numbers and sizes of their predators have decreased because the predators have been heavily harvested by humans. Once the predator numbers and sizes increase (following the establishment of a no-take marine reserve) the extent of these barrens decreases and the kelps return. This has been observed at Leigh (Goat Island) Marine Reserve where kina predators such as snapper and rock lobster have increased significantly in size and abundance since the reserve was established.

John Booth, chair of Fish Forever, has spent considerable time comparing changes between older aerial imagery and the detailed aerial images produced by the recent Oceans 20/20 study. He found that many sheltered and semi-sheltered shores now had kina barrens in areas that had tall kelps in the 1950’s. He was, however, unable to assess the current state for steeper shore lines, especially those on the exposed open coasts.

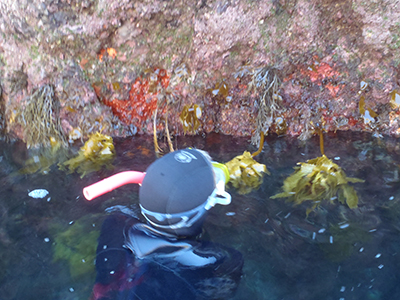

So Pacific Eco-Logic has been undertaking autumn surveys to help Fish Forever identify the extent of “kina barrens” on the shallow reefs of the Bay of Islands, and to provide baseline data against which future changes can be measured. Our focus has been the exposed and steeper reefs where aerial photography can’t provide interpretative assistance. We have also assessed semi-sheltered reefs around parts of Waewaetorea and Deep Water Cove.

So Pacific Eco-Logic has been undertaking autumn surveys to help Fish Forever identify the extent of “kina barrens” on the shallow reefs of the Bay of Islands, and to provide baseline data against which future changes can be measured. Our focus has been the exposed and steeper reefs where aerial photography can’t provide interpretative assistance. We have also assessed semi-sheltered reefs around parts of Waewaetorea and Deep Water Cove.

We had hoped to make our assessments during summer but the predicted drought and westerlies associated with an El Nino did not eventuate. The regular rainfall kept plankton densities and silt turbidity high, preventing deeper water snorkel surveys. Also the weather systems delivered a series of easterly or northerly winds and swells, which limited opportunities for shallow water surveys. However, autumn has provided periods of up to four days with water clarity and weather conditions suitable for the surveys.

To date we have identified (and geo-located on marine charts) over 260 representative quadrats along the shallow subtidal between Pig Gully (near Cape Brett) and Okahu Island. Each quadrat measures 5m x 5m and is situated in the depth zone where urchin barrens are most likely to be formed, namely between 3 and 9 metres deep. Vicky undertakes up to 4 free-dives on each quadrat to assess the % cover of a variety of vegetation and other cover types, as well as substrate, slope, exposure and representativeness class. Chris records all this information, as well as the depth sounder data, while trying to minimise the impacts of wind and swell conditions on holding station with the RIB.

Although the field survey work is not complete, and the data not yet analysed, there are some preliminary observations worth reporting at this stage. Firstly the “kina barrens” are not as easy to distinguish or define boundaries for as in some other areas. Generally they are considered to be areas where kina browsing has removed tall kelps and has maintained a cover of grazable turfs, algal felts, coralline paints, encrusting sponges or anemones. We concluded they were much patchier and smaller than our earlier observations had indicated, and therefore more difficult to map and monitor. In addition, we found that there was often a narrow band of kina barren shallower than 3m depth (usually 0.5 to 2.5m) in places where the kelp forests were sheltered from strong waves and surge.

Regarding the name “kina barren” we found that in a limited number of places the dominant urchin was the purple long-spined urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii), which is not the common kina (Evechinus chloroticus). Accordingly, we suggest that it would be more appropriate to use the generic term “urchin barren”, which is recognised internationally. One place where the purple urchins are particularly abundant (and large) is on “White Reef” at the entrance to Maunganui Bay. This is where many of the Canterbury wreck divers do their shallow dive or midday snorkel, and a number use the kina on the reef to feed the aggressive leatherjackets and increasingly large snapper. This may be contributing to an increasing dominance of the larger, longer spined urchin.

Rare and special marine habitats

The other assessment we are undertaking at the same time is to identify and report on the rare and special marine habitats of the Bay of Islands. These are generally not those which are representative of the widespread habitat types which are determined primarily by depth, substrate and exposure. They are instead the habitats for which the biological communities are most influenced by other factors, especially strong currents, up-wellings, low light levels, extreme topography, biogenic reefs/substrate or a combination of these. Although we have mapped and described a variety of these arches, caves, passages/slots, rhodolith beds and shellfish reefs in the eastern Bay of Islands, we need more information from divers and other readers about possible candidate areas in the southern and western Bay of Islands. These need not be your favourite cray dives, but rather an archway filled with jewel anemones and yellow zooanthids, or an undredged gut with horse mussel reefs! Please contact Vicky and Chris at