Quick facts

This is approximately what 500,000 t of sediment looks like by volume. Enough to create a pile on a rugby field 51 m high!

This is approximately what 500,000 t of sediment looks like by volume. Enough to create a pile on a rugby field 51 m high!

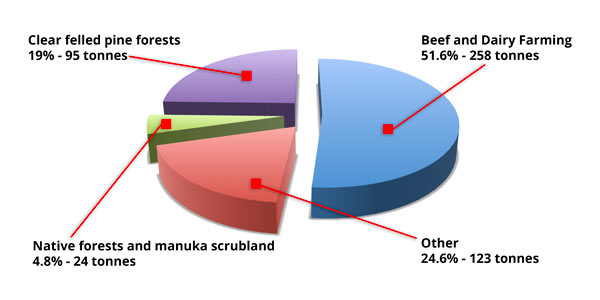

Break down of contributors to Bay of Islands sedimentation

Break down of contributors to Bay of Islands sedimentation

How much

- In the last 150 years, sedimentation has been 22 times greater than the last 10,000 years!

- Approx 500,000 t of silt surges down our rivers to be deposited in Bay of Islands waters every year.

- That's 2.4 mm on the seabed each year.

It covers shellfish beds, displaces kelp forests, turns rock seabeds to mud, and extinguishes important deepwater habitats.

Where it comes from

- Beef and dairy farming contribute 51%.

- Clear felled pine forests contribute 19%.

Native forest and manuka scrubland contribute a miniscule 5%, even though they make up 20% of the land cover.

What can we can do to reduce it?

Photo: Dean Wright / OneshotRiparian planting, wetland restoration, sediment traps – and generally being savvy about slowing rates of runoff during heavy rains – can reduce the dirtying of our waters and minimise sedimentation.

Photo: Dean Wright / OneshotRiparian planting, wetland restoration, sediment traps – and generally being savvy about slowing rates of runoff during heavy rains – can reduce the dirtying of our waters and minimise sedimentation.

[button style="color" href="https://www.nrc.govt.nz/Environment/Land/Managing-riparian-margins/riparian-planting/" target="_blank"] NRC has more information here[/button]

Fish Forever's sister working group Living Waters has three riparian planting projects currently underway, all volunteers welcome!

[button style="color" href="http://livingwatersboi.org.nz" target="_blank"] Visit Living Waters website here[/button]

[/panel]

Sediment Forensics

Photo: Dean Wright / OneshotIt’s known as sediment forensics. Geochemical tools and biomarkers allow us to identify the sources and dispersal of land-derived soils and reach an understanding over the way that sedimentation has built up on the seafloor.

Photo: Dean Wright / OneshotIt’s known as sediment forensics. Geochemical tools and biomarkers allow us to identify the sources and dispersal of land-derived soils and reach an understanding over the way that sedimentation has built up on the seafloor.

Where it comes from

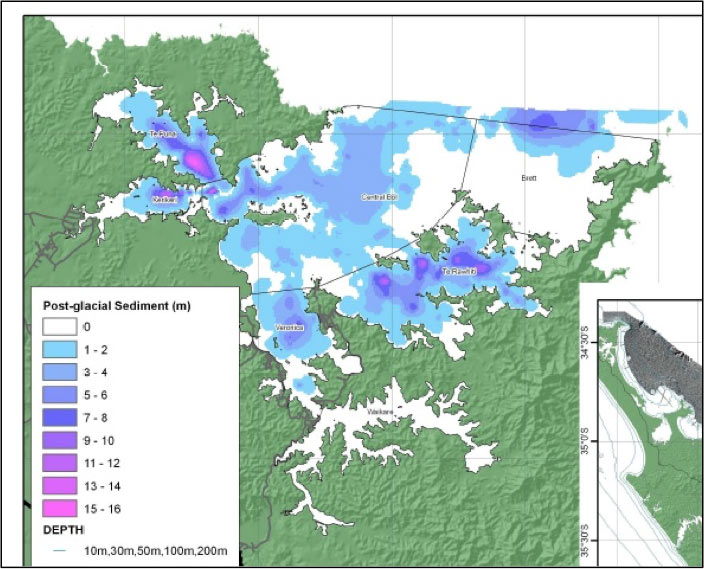

Not surprisingly, most of the sediment entering the Bay of Islands today comes from its major rivers - the Kerikeri, Waitangi, and Kawakawa. Silt from the Kerikeri appears to flow directly to the open sea, probably because of the constraining presence of Moturoa lsland - although the Kerikeri River is, too, a source of sediment for outer parts of Te Puna lnlet. Sediment from the Waitangi River mixes with that from the Kawakawa as it flows out through Veronica Channel - to then pass across the Bay to the open ocean, or around Tapeka Point and east into Te Rawhiti lnlet. And it’s here the principal dump in the Bay is to be found.

About half a million tonnes of sediment are deposited in the Bay of Islands each year. The largest catchment is that of the Kawakawa River (8), which is also by far the largest source of silt. The next biggest source is the Waitangi River catchment (7), followed by the Kerikeri (6). The Waipapa (5) and Waikare (9) are the other main rivers draining the Bay of Islands.2, 3

About half a million tonnes of sediment are deposited in the Bay of Islands each year. The largest catchment is that of the Kawakawa River (8), which is also by far the largest source of silt. The next biggest source is the Waitangi River catchment (7), followed by the Kerikeri (6). The Waipapa (5) and Waikare (9) are the other main rivers draining the Bay of Islands.2, 3

Te Rawhiti Inlet, with a depositional area of about 46 km2 and a relatively high average sediment accumulation of 3.2 mm/yr, is the single largest sediment sink in the Bay of Islands system, and accounts for 30% of the annual sediment deposition.4

Thickness of the sediment laid down over the past 18 thousand years (since the end of the Last Glacial Maximum), with depths in Te Rawhiti Channel (where much of Bay of Islands’ sediment ends up today) of 7-12 metres. (The extreme values indicated for Te Puna Inlet are highly uncertain).5

Thickness of the sediment laid down over the past 18 thousand years (since the end of the Last Glacial Maximum), with depths in Te Rawhiti Channel (where much of Bay of Islands’ sediment ends up today) of 7-12 metres. (The extreme values indicated for Te Puna Inlet are highly uncertain).5

What sort of land cover sediment comes from

When it comes to the sort of land cover from which all this sediment is derived, things are seriously out of kilter. More than three-quarters of the sediment from the Kawakawa, Waitangi, Kerikeri and Te Puna rivers and streams comes from grassland, yet the area of land in grass in these catchments averages only 50%. In contrast, less than 4% of the sediment from these rivers comes from native forest, which has an average land-coverage five times that. For the Kawakawa River and Te Puna Inlet, a third of the sediment comes from pine forest, which covers only one tenth of surrounding lands.5

Most of the annual sediment load for the Bay of Islands as a whole comes from pasture used for beef and dairy farming (258 000 t) and pine forest that has been clear-felled (95 000 t). Other pasture land-use sources combined contribute about 50 000 t. On the other side of the ledger, native forest and kanuka scrubland contribute a miniscule 24 000 t.5

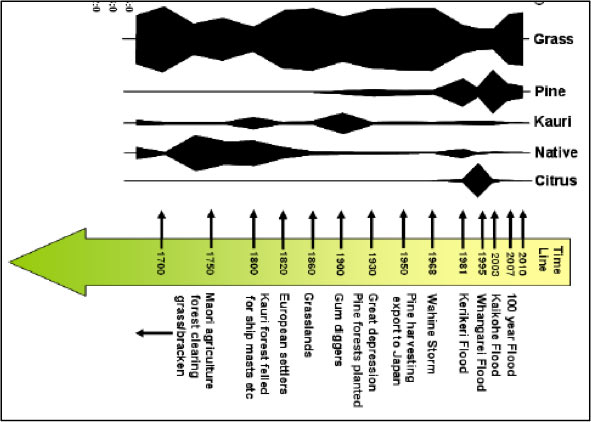

Sediment cores from within the river deltas provide a time-line of land use. Around 1800 there was an increase in the proportion of sediment containing kauri-forest signatures, which coincided with soil disturbance associated with harvesting kauri. The increase again in kauri-forest signatures around 1900 may have coincided with soil disturbance by gum diggers and the draining of kauri swamps. The presence of pine forests was identified in the sediment from around 1920, the amount of pine forest-sourced soil increasing after the 1960s and consistent with the history of forestry in the area.5

Time-line of signatures denoting various land-use, based on a sediment core in Veronica Channel.5 (The huge 1981 Kerikeri flood appears to have had little impact at the sampling site.)

Time-line of signatures denoting various land-use, based on a sediment core in Veronica Channel.5 (The huge 1981 Kerikeri flood appears to have had little impact at the sampling site.)

References

1. Gibbs, M.; Olsen, G. (2010). Bay of Islands OS20/20 survey report. Chapter 5: Determining sediment sources and dispersion in the Bay of Islands. http://www.os2020.org.nz/

2. MacDiarmid, A. plus 26 others (2009). Ocean Survey 20/20. Bay of Islands Coastal Project. Phase 1 – Desk top study. NIWA Project LIN09302. http://www.os2020.org.nz/

3. Northland Regional Council (2012). Sate of the environment report 2012.

4. Swales, A.; Ovenden, R.; Wadhwa, S.; Rendle, E. (2010). Bay of Islands OS20/20 survey report. Chapter 4: Recent sedimentation rates (over the last 100-150 years). http://www.os2020.org.nz/

5. Bostock, H,; Maas, E.; Mountjoy, J.; Nodder, S. (2010). Bay of Islands OS20/20 survey report. Chapter 3: Seafloor and subsurface sediment characteristics. http://www.os2020.org.nz/